I have a good excuse for having stayed away from the blog for some time: I was busy getting ready for the 8th European Conference on African Studies which took place at the University of Edinburgh last week. This was my first ECAS, and with 1,500 participants and hundreds of panels, it was almost overwhelming. My impression of this mega-conference remains very partial, since even with the greatest stamina it was only humanly possible to sample a very limited selection of what was on offer. My interests were divided between sessions on decolonisation, increasing exchange with Africa-based researchers, and of course panels dedicated to language, on which I will focus in this post.

Diversifying outlooks and epistemologies requires equal access of researchers to resources, discourses and debates. The obstacles are manifold, but one is keenly felt in the UK at every international scholarly gathering: the difficulties for African researchers to obtain visa. For the panel that I co-organised with my colleague Fiona Mc Laughlin, this meant that one of the African participants could not deliver his talk in person, since his visa had been refused. This is not an isolated case: visa refusals have dramatically increased since the introduction of the hostile environment to immigration. The anger at this persistent injustice has prompted leading researchers to write an open letter about which you can read here.

It is impossible to think African languages without thinking multilingualism, and all panels I attended shed light on its various aspects. Fiona Mc Laughlin’s and my panel “Language and the political imagination – connections and disruptions” featured three talks (panelists from Zimbabwe had to withdraw their participation), each of which laid bare how multilingualism is negotiated even at the smallest local scale, and how diverse the motivations are for associating a language with a place.

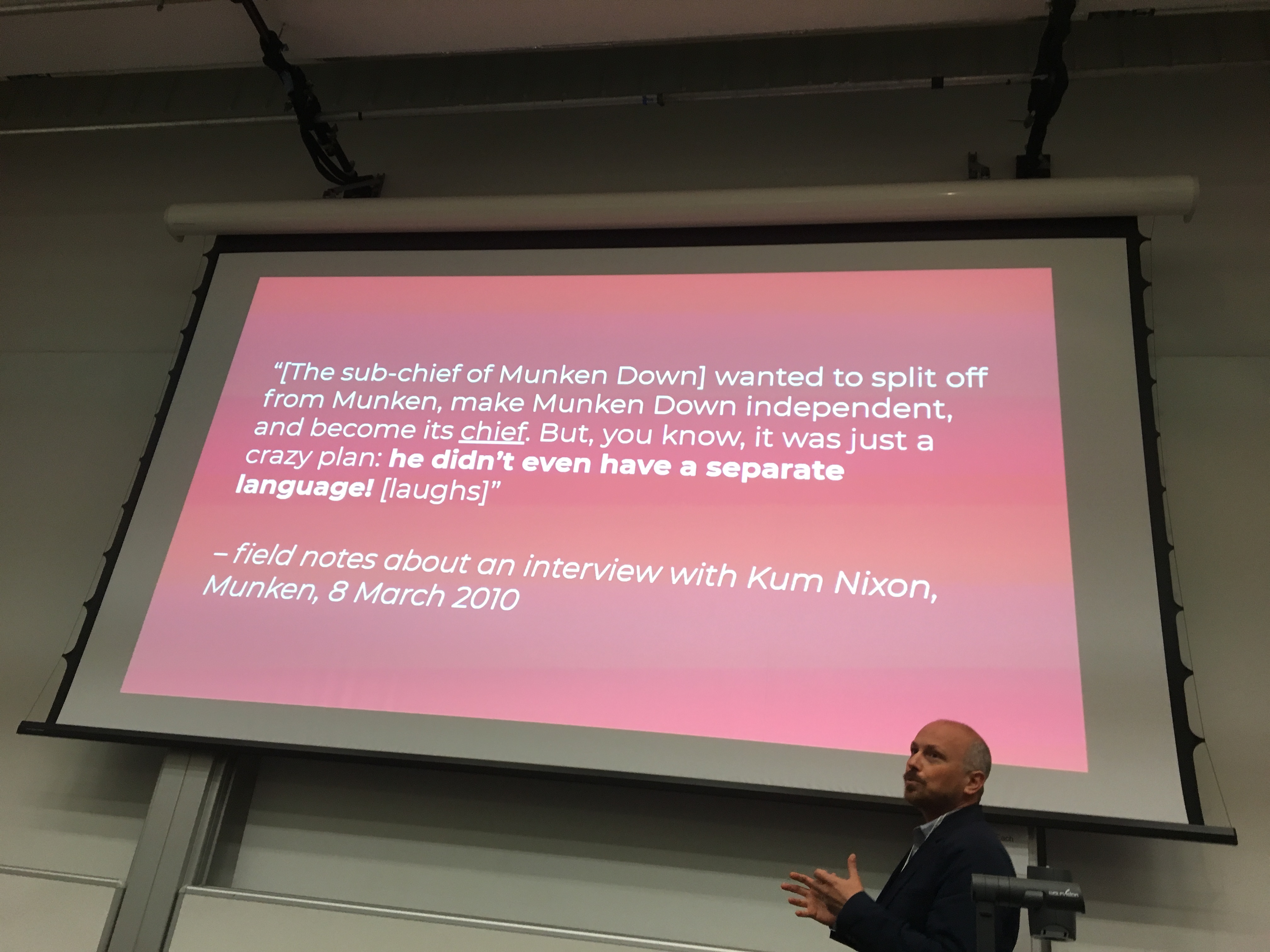

In my own talk “Putting the history back into the speech community: firstcomer-newcomer dualisms and language territorialisation” (the title being a nod to Paul Nugent’s paper “Putting the history back into ethnicity: enslavement, religion and cultural brokerage in the construction of Mandinka/Jola and Ewe/Agotime identities in West Africa, c.1650-1930′”) investigated how the languages of firscomers who settle strangers and control the land rights in linguistically heterogenous places can over time become re-imagined as the ethnic languages of entire spaces. The second talk, set in the Western Cameroonian grassfields, by Pierpaolo di Carlo and Ivoline Bidji Kefen showed the process of language territorialisation in the making through illustrating how a language, however minimally distinct from its neighbours, becomes a tool for the constitution of a political unit.

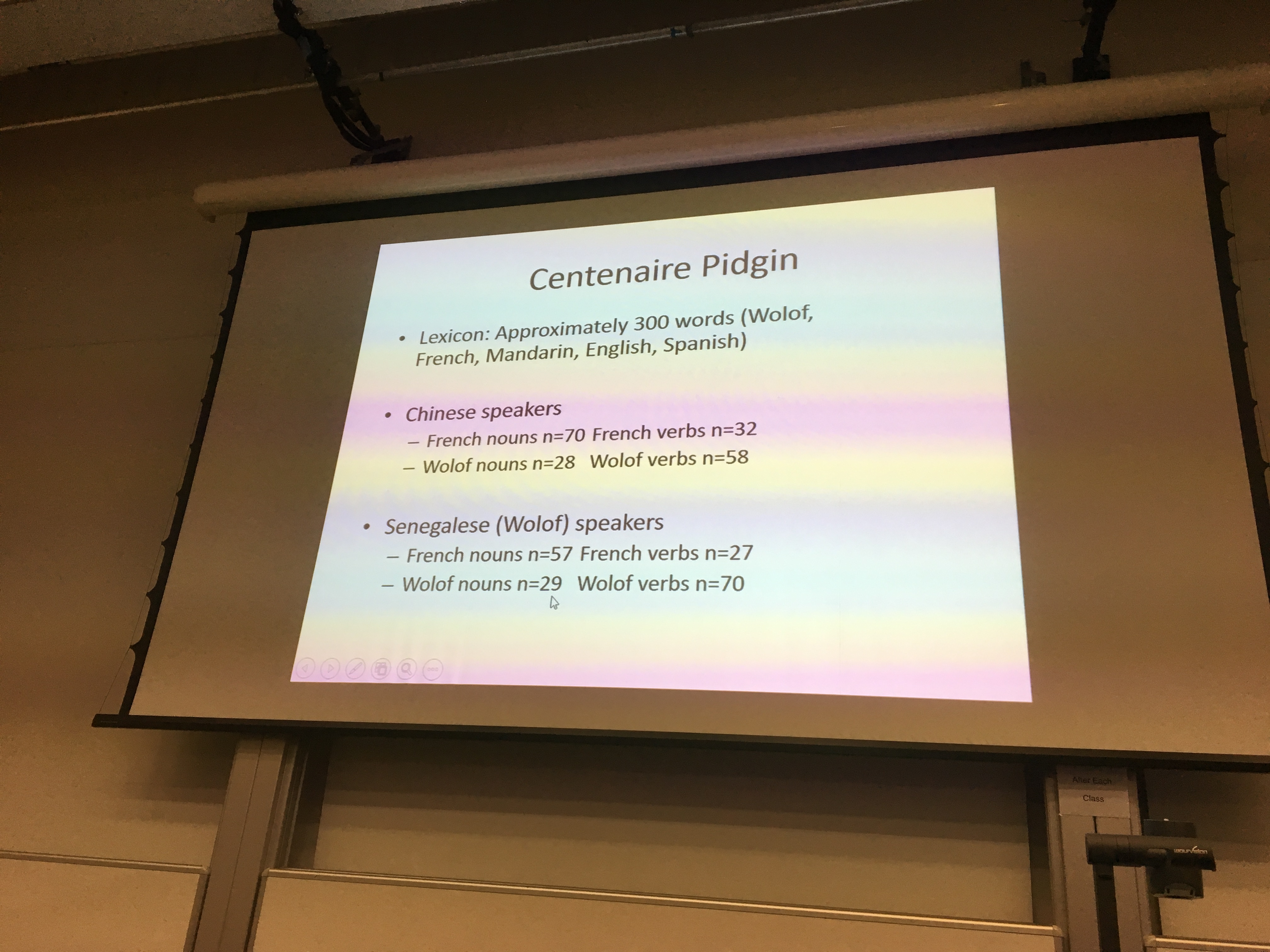

Fiona Mc Laughlin’s presentation on emerging multilingual language practices in Dakar’s Chinese market forcefully illustrated the great willingness of stallholders and customers to forge practices acknowledging their interlocutors’ linguistic profiles by creating a pidgin that reflects their interactions, not for mere communicative needs, as she argues, but as playful and creative practice in a shared sociolinguistic space.

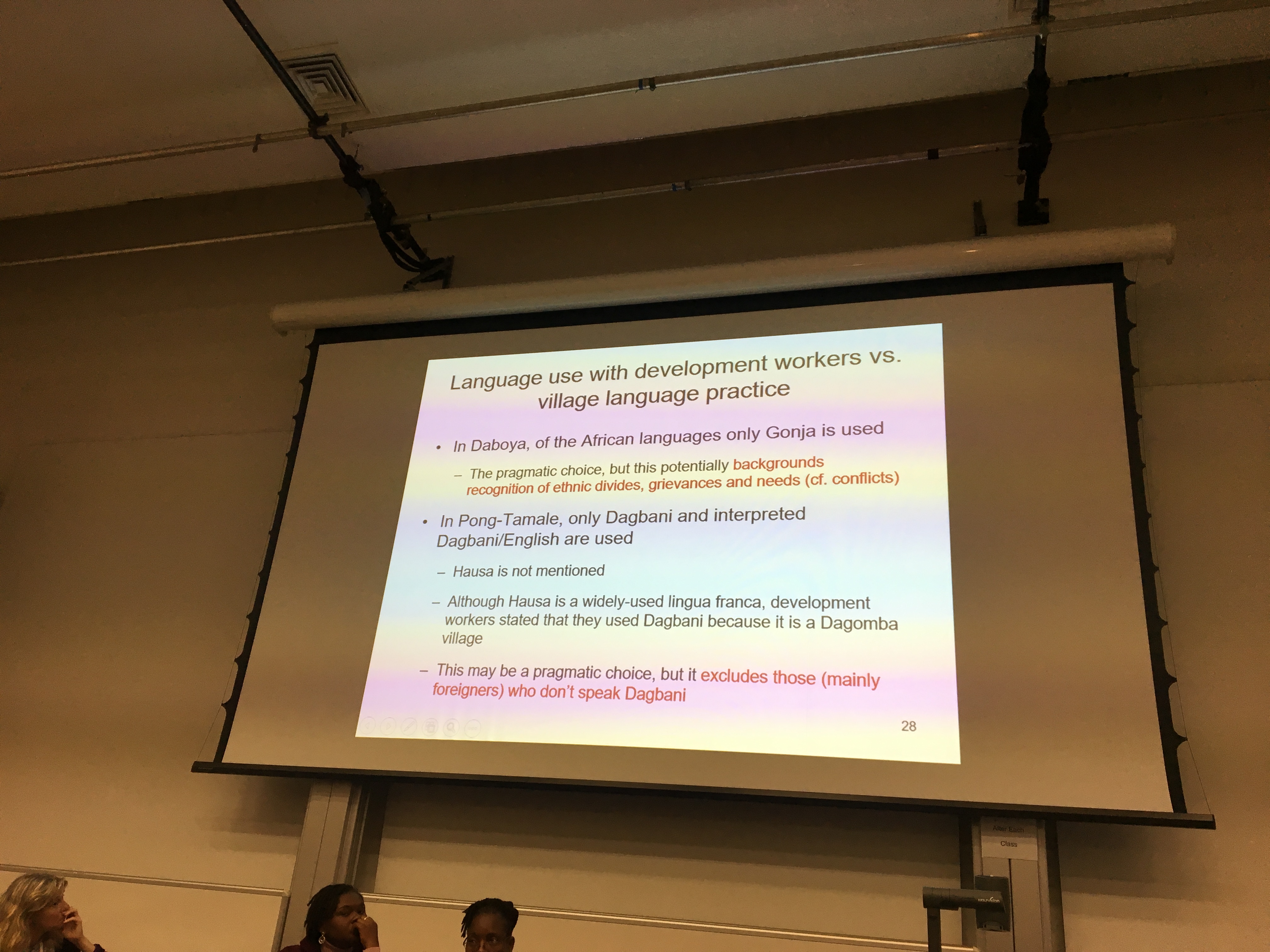

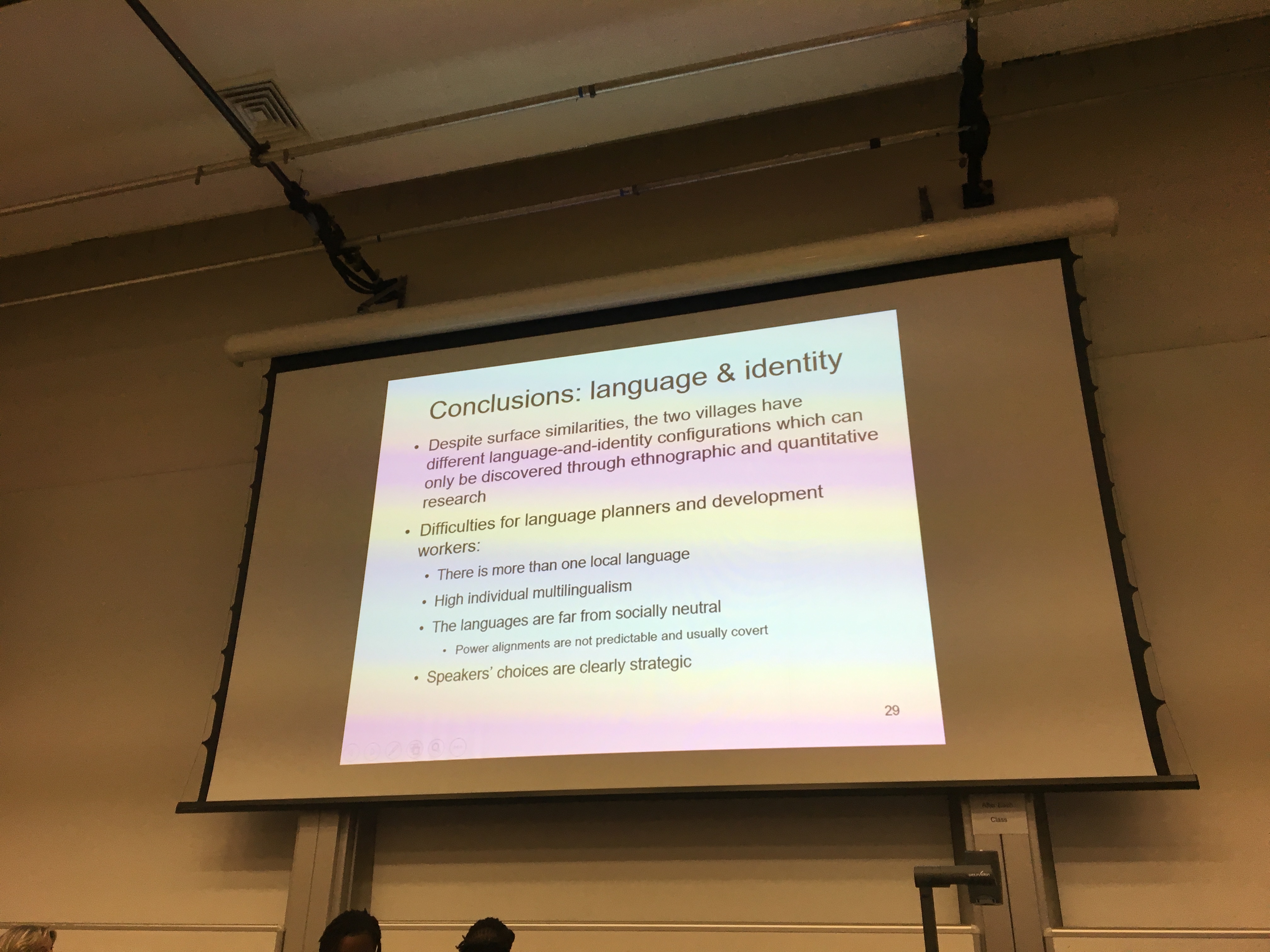

In a different panel, Paul Kerswill’s and Edward Salifu Mahama’s talk on the great differences in multilingual organisation in two rural settings in Northern Ghana resonated with these talks in highlighting the need for detailed ethnographic and historically embedded studies in order to apprehend the significant differences in patterns of multilingualism in two geographically very close yet distinct settings.

On Friday, a panel on the disruptions concerning the use of indigenous languages oscillated between observations of versatility and trauma. Elise Solange Bagamboula’s paper “Modernisation et l’émergence de nouvelles pratiques langagières en Afrique sub-saharienne: vers une analyse glottopolitique du cas de la Rébublique du Congo” was dedicated to the adaptability of both ethnic and linguistic configurations to new circumstances, including the growing presence of Chinese investors. But Mathias Bwanika-Mulumba and Taiwo Oloruntoba-Oju deplored the continuing disinvestment in indigenous languages, the fact that their teaching remains tokenistic and their prestige non-existent in the face of English. A testimony of the continuing pain and exclusion induced by colonial language legacies and also, as Bert van Pixteren reminded the audience in his talk, an enormous waste of talent.

Yet, colonial languages can also be creatively appropriated, and the afternoon offered a delightful taste of that. The film Frontières, by Burkinabé director Apolline Traoré, vividly portrayed how colonial borders persistently endure in her road movie. It features four women on a perilous coach trip from Dakar to Lagos, suffering the harassment and dangers ever-present at West Africa’s postcolonial borders despite the promises of free movement of the ECOWAS space. Of great interest to linguists, the film also illustrates linguistic borders, testifying of the colonial partition of Africa. But it also shows how these borders are overcome in the languaging practices of its protagonists. This theme, the erasure of boundaries through creativity, ends my ECAS experience: the truly transcendental Scottish-African Ha Orchestra closes the conference with a concert interweaving various musical traditions and musical and spoken languages, juxtaposing flute, mbira, kora, djembe and sintir. Although the spectres of physical and linguistic colonial borders continue to haunt Africa and Europe, artistic and linguistic resilience is there to build bridges, and I travel home with some hope and many new connections.